Simon here forms the start of a short series of posts on those Ginns of Aston who while clearly related to, are not descended from, the William Ginn of Aston in my post of 22nd June 2012. .

We have seen that Thomas Ginn, yeoman of Aston in the mid 1440s was the first Ginn there. It logically follows that the Aston Ginns that followed are all descended from him

We have also seen that that Thomas had what had been the demesne farm, ie the farm of the Lord of the Manor and that Reading Abbey, then then Lord, had granted this copyhold to the Ginns back in the 1400s, when amazingly (this is so far back) the Plantagenet line were still Kings of England. But there was a catch. Medievalist Professor Mark Bailey has pointed out to me that because this was demesne land, if the Ginns did not have a male heir in succession, for even one generation, then the whole farm, the whole 220 acres reverted back to the Manor. So it was essential for each generation of Ginns to ensure that this did not happen.

Now the standard manorial rule for inheritance was primogeniture, ie everything went to the first born son. Simple. But what if you were not sure who was the first born son - what if there were twin sons. That seems to have been the fate that hit the Estate of Thomas Ginn of Aston when he died in 1526 - see post June 22nd 2012 ) Because Thomas left his farm in his will to his son William whose claim was "by right" said Thomas. But the Manorial Court differed. Thomas Ginn's widow Joan (by now remarried to Laurence Benn) thought that the heir should be John Ginn, William's brother. There was an argument as to who was born first. The implication also is that William was not yet married, John was. John it was said was to provide for William as long as William needed it, and provide William with some money and farm animals as compensation.

The implication has always been that they were not sure who was the eldest son. And perhaps the family wanted to make sure that they "bet on the right horse" giving inheritance to a married man with children, not risking losing the farm to the Manor by giving it to a bachelor. This sort of thing on top of the weather, blight and pests was one of the worries that beset Tudor farmers.

But it is pretty clear that by the 1530s William had married (this is before parish registers) and it seems equally clear that Simon Ginn here and a daughter Alice were two of the children, probably the only two that survived. I first researched this back in the early 1990s.

I am as English as they come says my Ancestry DNA, but have always been a Republican (not much time for the Royals) but, oddly Elizabeth the 1st (Good Queen Bess) has always been something of a heroine of mine, she was quite a woman. And oddly, by a quirk o fate, Simon Ginn and the Queen entered this world roughly at the same time and left it almost together.

Simon Ginn was born in about 1533 - no baptism entry survives of course, it is too early. He would have been born in a cottage pretty much like that in the cutaway image below, with a Hall (living room) with an open fire venting smoke through a hole in the roof, a Chamber (a downstairs bedroom/sleeping quarters) and (the houses were only designed for one storey) a loft area squeezed in above to which access was gained by a ladder and used for storage or sleeping, in the latter case it would have been flat truckle beds on the floor or mattresses - straw, flock (cut up wool) or feather (for those with some spare cash) piled up, there would not have been the height for a standing bed or four poster.

As the Tudor era advanced, brick chimney stacks came to be built for even ordinary people, the hole in the roof was closed off (a major fire hazard removed) and the chimneys allowed the creation of upper storeys and by opening the chimney stack on the upper floor the creation of fresh hearths and heating there. In most houses, even cottages, a staircase to facilitate this was squeezed in and the upper storey was used for further chambers/bedrooms, but these would have had height restrictions, they were squeezed into the house, and a standing man (men were luckily shorter then) would have had to duck quite sharply to avoid hitting his head.

But the cottages were havens for disease. The ground floor flooring was beaten earth, it was covered with strewn rushes or straw or sawdust and these were no bathrooms of course and people scarcely washed. There was a constant musty, unpleasant smell and insects and small rodents lived in the detritus on the floor. Disease was literally living in most houses waiting for an opportunity to develop. The Dutch theologian Erasmus visited England several times in the 1500s, he suffered from ill health and craved cleanliness and ventilation, his thoughts on English houses follow.......

"The floors are, in general, laid with white clay, and are covered with rushes, occasionally renewed, but so imperfectly that the bottom layer is left undisturbed, sometimes for twenty years, harbouring expectoration, vomiting, the leakage of dogs and men, ale droppings, scraps of fish, and other abominations not fit to be mentioned. Whenever the weather changes a vapour is exhaled, which I consider very detrimental to health... I am confident the island would be much more salubrious if the use of rushes were abandoned"

Not very pleasant then.

Simon Ginn married Marion Hyde at Aston in 1562 - four years after Elizabeth the First ascended the throne. It is unclear if Marion was an Aston girl. They stayed in that parish and it seems obvious that Simon inherited his father William Ginn's freehold cottage which would have given him the vote as a freeholder, in a time when scarcely one in ten men could vote. This would have also given him some status and Simon referred to himself as a Yeoman, but though born to that class Simon was at best a Husbandman. The couple did not have that much money, but the records make it clear that these were decent people, they tried to do the proper thing, and that is just about the best that can be said about any of us.

I know quite a lot about their living conditions. Whether they lived in Aston or Aston End (nearer Stevenage) seems unclear. But although Simon and Marion may have had a chimney put in the house (and even that is arguable) they never created a proper second storey, the conversion was fairly basic as no staircase appears to have been put in, just two lofts were created above two rooms and nothing over the Hall. On the ground floor was the Hall and a Chamber and a small Buttery (where the butter was churned and the Cow (they had a black cow) milked. There was a loft above the Buttery and one above the Chamber - both presumably accessed by ladders (there were three ladders in the house). So they still only had a fire in the Hall and may still have had that open to a hole in the roof. There were two beds and mattresses and bed linen (mostly towen rather than flaxen - towen was cheaper) in the loft above the Chamber and two beds etc in the Chamber itself. This is a cottage that I know at one time accommodated seven adults, so people (as was common at the time and later) shared a bed - hopefully not with the maid/relation who helped out (see below). Out the back were a few sheep and scattered geese and hens like in the illustration above.

It must have been tough. I am sure Simon had a field or two or the equivalent, but I doubt he held much land. He had the right to turn animals on the common and to gather wood from it, but it would have been a hard life - never quite being sure that the next meal was coming - all they really had was the cottage.

But the couple had four sons, and it is a tribute to Marion and her niece by marriage (see below) that they brought all four sons to adulthood if not middle age, Marion kept disease out of the home.

Simon Ginn was close to his sister Alice. She is the subject of the next post. She had married in 1559 and had children, but lost her husband soon after, then remarried a William Chilterton at Aston in 1565, had five further children by him and then he died aged 50 or so in 1578. Alice died in late 1579 leaving a whole string of orphans, many of primary school age. She left a will and made brother Simon her executor.

Simon and Marion clearly did the decent thing and took care of some of the children - they scarcely had room. One child, Marion Chilterton (probably named after her Aunt) was barely eight when Alice died, and Simon and Marion clearly took her in. She stayed with them for at least two decades and in time helped Marion Ginn around the house and I suspect became something of a sister to the four Ginn boys, her first cousins.

Simon and Marion saw out virtually the whole of the reign of Elizabeth the 1st together, enduring flood, storm, very harsh winters and living through the great victory over the Spanish Armada in 1588. It is quite likely that some of the Ginn boys were in the Militia, the records for Aston do not survive.

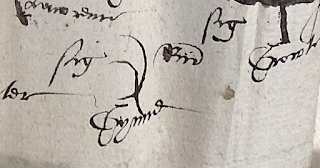

Original Will of Simon Ginn - signature below

At the time of Simon's death all four sons still lived in the house, the youngest was 29; either Marion had made them all too comfortable, their sexuality was an issue or none of them could afford to strike out on their own, perhaps a combination of all of the above.

Simon left the cottage to Marion for life and then to his eldest son William (aged 40 in 1603) and small sums to the other three children, a ewe to Marion Chilterton.

Marion Ginn lived on through the ill fated Gunpowder Plot of 1605 and died at the end of 1609 when she would have been about 72 given her age at the birth of her youngest child. Her will was made of Christmas Eve .

Her Will and Inventory (Herts Archives) are informative, they are how I know so much about the living arrangements. All four sons were then still alive and Marion was concerned that those at home were OK providing that "the table in the haule and the forme and the cobbard shall remayne there for so longe as anye of my said children shall remaine in the house". William got the black cow and, obviously, the cottage, but a sibling or two was still there. The original will with her signature survives (below)

The children of Simon and Marion

William - he was 46 when his mother died and clearly not married. He inherited the cottage according to his right but it was obviously later taken over by his younger brother Thomas so he died without issue, There is no burial entry that I can find.

Robert - he was also alive in December 1609 aged about 43. I have always considered him (but cannot prove it) the Robert Ginn who went to neighbouring Walkern, being in the Muster records of 1605 having gone there after his father died. That fellow married Mary Burdett in Walkern in 1608. Robert would then have been 42 and it seems likely that Mary was of a similar age because there were no children. Robert died at Walkern in 1625 aged about 60.

Walkern by legend is so named because when the church was being built the stones laid mysteriously moved each night after the masons had left. It was considered the work of the Devil and the Hertfordshire locals told him to "walk on!". In 1711 it was the scene of one of the last witches in England to be condemned to death - Jane Wenham - who lived in a hovel in the village. The sentence was commuted and she lived out the rest of her life in peace, the case having caused a public outcry and leaflets (below) published in her defence.

Edward - was alive and 38 in December 1609. I am sure he was at home. There is no evidence of marriage or children and I am equally sure he died without issue because his brother Thomas inherited the cottage. There does not appear to be a surviving burial record.

Thomas - born in 1574 is the only of the four brothers who may well have descendants alive today - though they likely do not know it. We will deal with him shortly

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)